The character of the Christianity that grew in the New World was an amalgam of Christianity and indigenous rituals. The Spanish crown's ideologues (the Catholic Church) were well aware that there would be remnants of the old religion even among the sincerely converted; it used the Inquisition to curb the most obviously incompatible behaviors, such as concubinage and bigamy, but hoped that syncretism would serve to create a new culture that would be acceptable to the Indios. Moreover, since the invading force was short on administrators, the Spanish used indigenous administrators to help keep order in the New World. In this way, the Spanish hoped that they would avoid rebellions of the conquistadores and the Indios.

The Archivo General de La Nación (Mexico), Inquisitión, Tomo 37, describes idolatry, sorcery and sacrifice in central Mexico and Oxaca during the 1530's and the 1540's:

"... the Indians attempted to manipulate inquisitional procedures by denouncing Spanish-appointed caciques [Spanish title for indigenous leaders] of idolatry in order to deprive them of office. There are also denunciations for idolatry and human sacrifice by Indians who wanted to attack their own political enemies hoping to replace them in a new political hierarchy. The procesos also illuminate subversive activities or Indian sorcerers, curers, witches, and seers who tried to perpetuate the old beliefs. Of particular concern to the Mexican Inquisition were groups of native priests and sorcerers who openly defied the 'spiritual conquest' by establishing schools or apprenticeships among the young. The teachers made a frontal attack on catholicism and Spanish culture. They ridiculed the new religion and urged a return to native religious practices. These men, branded as 'Dogmatizers' by the inquisitors, were considered especially dangerous by the missionary clergy. ... They supported the ancient practices of concubinage and bigamy as a symbol of resistance to the new religion — and the dogmatizers also ridiculed the Inquisition. Students of ritual humor among the Maya ... found survivals of plays and dances done in jest of the Holy Office. ... It is obvious that the same set of attitudes impelled native doctors or curers [curanderos] to continue the use of pre-conquest medicine, and to transmit Aztec, Maya and Mixtec medical lore to future generations of Indians and mestizos in colonial Mexico." 1

"In Chichicastenango the war between Alvarado and the Quiché is enacted. Among the Chortí it is called the Dance of the Huaxtecs, and represents the battle between Cortés and the Huaxtecs, who are called Black Men. Click here to see the dance. A man impersonates Cortés's interpreter, Malinche. ... Two variants of this dance are performed in Jacaltenango, 'the Cortés relating to the Conquest of Mexico ... [and] ... the Moors telling of the wars between the Spaniards and the Moors.'" 2

"The Cacique of Matlatlán was judged in November, 1539, for idolatry, concubinage and for sacrificing chickens during the native feast of Panquetzalistli."3

"In 1774, [the Mexican Inquisition] investigated sorcery in Huamantla and Huauchinango, and it moved to suppress the native dances 'Santiago' and 'Temascles' throughout Mexico." 4

"In 1623, Antonio Prieto Villegas, Inquisition Commissioner for the province of Zapotitlán investigated the Achí of his region who were performing prohibited dances, especially the Tum-Teleche, a pre-conquest tragic dance-drama." 5

"Important to future studies will be analysis of peyote cults and the use of other hallucinogens (yerba pipizizintle, ololiuqui) in idolatry, sorcery and in other patterns of pagan resistance." 6

One must consider that Fray Bernardino de Sahagún served as consultant and interpreter to the 1530 Inquisition, " ... the connection between Fray Diego de Landa's 1562 trials of Maya indians and his learned treatise on the Maya. ... Hérnando Ruíz de Alarcón's 1629 studies of paganism and religious syncretism in south central Mexico also related to his position as Commissary of the Inquisition there, and Gonzalo de Balzalobre's 1656 Report on Oxaca Idolatry stemmed from his probe into paganism and recurrent idolatry ..." 7

"[E]thnohistory for the anthropologists is essentially historical ethnography created from documents rather than direct informants..." 8 "Perhaps the thorniest problem faced by an ethnohistorian as he intreprets Procesos de Indios relates to ... the art of determining the validity of historical sources. Do the Inquisition manuscripts give a reliable picture of native religion or pagan resistance? Did the monastic inquisitor or the proisor or the professional judge on the Holy Offie Tribunal correctly understand the testimony and the evidence? Did the inquisitor project a image or an interpretation of data in the Procesos de Indios from an ethnocentric Christian viewpoint? ... Were the interpreters really competent to transmit testimonies of Indians who did not know Spanish?" 9

"Between June and October 1536 the Bishop [Zumárraga] tried two dogmatizers and sorcerers who also trained young men to become pagan priests. Tacatetl and Tanixtetl of Tanacopán, Hidalgo, practiced idolatry, sacrificed to the rain god Tlaloc, and used ritual paraphenalia including a tonalamatl [native manuscript]. Between November 1536 and March 1537, a famous sorcerer and soothsayer who roamed the villages in Texcoco, Hidalgo, and Tlaxcala named Ocelotl (Martin Ucelo) fell under Zumárraga's censure. Ucelo used hallucinogens and dogmatized against the friars. Mixcoatl and Papalotl, intermediaries in sacrificial rites to the rain god and to Tezcatlipoca, were sentenced in December, 1537. Violent foes of the missionaries, they preached sermons against Christianity and urged the Indians to resist baptism." 10

Between October 1539 and March 1540, Zumárraga brought to trial several Indian caciques "who openly flaunted the new religion and set a bad example for their subjects." One cacique got intoxicated (in the traditional Indian ceremonial fashion) and performed pagan marriages; another was charged with idolatry, concubinage, and for sacrificing chickens during tne native feast of Panquetzalistli; another was tried for making sacrifices (including human sacrifices) to the rain god, Cocijo; the Cacique of Tlapanola refused to allow his subjects to go to mass and drove them away from the church by force; "[t]he dogmatizers Marcos and Francisco of Tlalteloco criticized the teachings of the Franciscans and cast aspersions on their sexual mores. They ... attacked the sacrament of confession claiming that the friars, not God, were curious about sin." 11

"After the Zumárraga period — he was removed as Apostolic Inquisitor in 1543, but he continued as Bishop and Ecclesiastical Judge Ordinary until 1548 — inquisitors and bishops proceeded mildly against Indian relapses into paganism. Most of the important prosecutions of Indians took place in Oaxaca and Yucatán from the 1540's through the 1560's. 12 Even though the new Tribunal of the Holy Office created in 1571 was prohibited from prosecuting Indians, the Inquisition continued to investigate paganism and to compile dossiers on Indian heresy. 13, 14

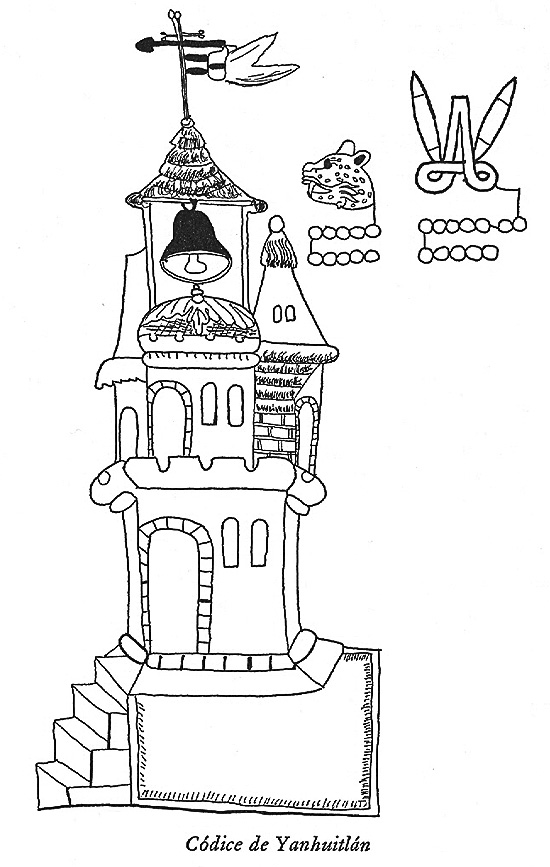

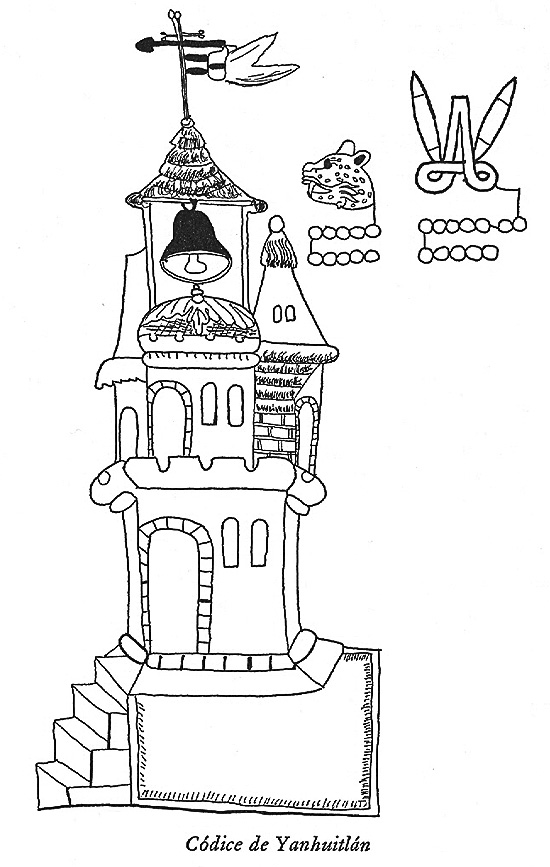

"In the years 1544-45 the cacique [Spanish name for an indigenous leader] and two high-ranking nobles of Yanhuitlán were brought before the Inquisition on charges of heresy and the continuing practice of native religion. ... It reveals traditional native religious practice and indicates the probable concurrence of pre-Hispanic religious practices with acceptable Roman Catholicism." Note that a cacicazgo was the Spanish name for an indigenous Indian kingdom that survived the Conquest. 15

"Don Juan [an indigenous noble of Yanhuitlán, after he was taught, baptized, and instructed in the Christian doctrine, reverted to the customs of exercising and performing his pagan rites, ceremonies, adorations, and sacrifices, and of having idols [Cauy, Poco, Quahu] and adoratories for them, both in his house and outside of it in many parts and secret and hidden places, and of having native priests [called Xihua] and custodians in charge of them, to care for and venerate the said idols. And Don Juan came often with other caciques and principales to honor them. And he sent other people to the market place and to the vendors of the said province to buy quail and pigeons and other birds and dogs to sacrifice and offer to their idols with copal, feathers, stones, straws, paper, and bowls, and this was done often. And often he sacrificed blood taken from his ears and private parts with stone needles and blades, offering it to his idols in order to obtain knowledge about them, and to learn of the things of the past from the priests, and to insure fortune and success in his undertakings." 16

"He sacrificed and offered sacrifices, in said shrines and adoratories of the idols, and in other places, many Indians and slaves in honor of the devil and in reverence for him, and especially, some ten years ago at the death of his mother-in-law when he had a girl sacrificed; and some eight years ago at the time of the great hunger the said Don Juan and some other principles ordered that five boys be sacrificed; and some five years ago he ordered the sacrifice of another girl; and about four years ago he killed and sacrificed a boy and buried him in his own house; and some three years ago when there had been no rain he sacrificed two more boys; and there are many other people that he has sacrificed in many divers times and places as offerings to his idols and demons." 17

"And the said Don Juan, after his baptism, has been in the custom of summoning the machuales [class of people between pipiltin or nobles, and slaves: the common people] of the said province and pueblo of Yanhuitlán who have received holy baptism, and several times he has told them and persuaded them that the doctrine as revealed and taught by the Christians and the baptism that they received were and are a mockery and a lie to which they should pay no attention, but that they should again honor their idols as they once did." 18

"Another thing which he specially advises is to observe and celebrate the days and feasts of their idols as they were accustomed to do in times past, honoring the idol of water which is called Zaaguy, and another that is called Tizones who is the god of the corazón, and another called Toyna, and another called Xiton which is the idol of merchants, these being the feasts which the said Don Juan has celebrated many and divers times, by himself and with others, with their rites and ceremonies, dancing and singing as well as by day, consenting to and partaking in the sacrifices and offerings to his idols, invoking the devil and his assistance in the manner of his paganism." 19

"And the said Don Juan, being baptized, and who until now has concealed and participated in heresies, especially those of Don Francisco and Don Domingo [cacique-regent of Yanhuitlán], cacique and principles of the said pueblo, and of others that were and are native priests, custodians, and guardians of the said idols and their sacrifices and heresies, has remained silent and has likewise concealed information about the persons who have made sacrifices with him, and he with them, and saw them done, and did them jointly and separately, all in contradiction to God our Lord and our Holy Faith." 20

Circa 1653, Catholic priest Gonzalo Balsalobre discovered that indigenous Indios were still practicing native religious beliefs: idolatry. (Note that this was 125 years after the Conquest.) The Indios consulted native priests and they in turn consulted "books". Balsalobre ordered an Episcopal Inquisition, and had these "magical books" destroyed. 21 Balsalobre observed that the indigenous Indios had teachers that taught them idolatry and sacrifices to the Devil of dogs and chickens, using copal (incense), with 24-hour long fasts; and that the Indios made seasonal sacrifices. He noted that the Indios worshipped 13 gods and goddesses; that they celebrated a year that had 260 days (13 months, each 20 days long); and that the the 260 days were comprised of four "Lightnings" of 65 days each (five gods in each Lighning). 22

Balsalobre described these thirteen gods and godesses as follows: 23, 24

| Ordinal | God or Godess | Assigned purpose | Sacrifice |

| 01 | Locucuy | Maise and food | |

| 02 | Lociyo | Lightning | Chili |

| 03 | Coqueelaa | Cochineal and Nopal cactus | White hen |

| 04 | Niyohua | Hunting | White hen |

| 05 | Nocana | Ancestors | |

| 06 | Nohuichana |

Pregnancies, childbirth,

fishing |

Copal, wax candles

(also candles in church for the Virgin: syncretism) |

| 07 | Lera | Sickness | |

| 08 | Acuece | Medications | |

| 09 | Lexee | Sorcerers, dreams, auguries | |

| 10 | Nonachi | several happenings | |

| 11 |

Coqueetaa,

Leta ahuila, Coqueehila |

Supreme Lord of Hell,

god of Hell, lord of Hell |

|

| 12 |

Xonaxihuilia

(godess) |

Sacrifices for the dead | |

| 13 | Leta acquichino | 13 |

"Like the expansionist Inca and Aztec empires before them, the Spaniards attempted to use the principle of indirect rule as much as possible. Where available, the Spaniards tried to preserve as much of the native aristocracy as survived the initial conflicts and were willing to accept a submissive role." 25 - 33

"In a deliberate attempt to preserve and exploit the resources of the Aztec, Maya, and Inca peasant masses, the Spaniards decided that local self-government, carefully controlled from above, represented an ideal arrangement. Thus the Spanish government proposed that the Indian communities elect their own leaders on an annual basis and syncretized preconquest forms with classical Spanish offices." 34

"... the prime function of these administrations was exploitive. These elected village elders, at no administrative expense, maintained local order, diverted latent Indian hostilities, resolved the vast amount of intra-community law disputes, and, most important, effectively guaranteed the exploitation of the local resources in the form of tribute and taxes. ... Not only did the peasants provide the Crown with tithes and tribute, they also supplied corvee labour for regional governments and various encomienda obligations to local Spanish colonists." 35

"Nevertheless, despite all the controls built into the system, once in a great while the structure was ripped apart. In the sundering of the governmental institutions which occurred, rebellious Indians were sometimes able to turn the local civil-religious hierarchy into a fully developed intercommunity. ... One of these few revolts illustrative of the potential of the civil-religious hierarchy to function as an independent government was the independent republic set up by the Tzeltal Indians of the chiapis highlands at the beginning of the eighteenth century." 36

"While the Tzeltals, in the majority, owned their own lands through their community governments, they were, nevertheless, ruthlessly exploited and taxed by the Spanish civil and church authorities and were maltreated as well by the ladino urban merchants." 37

"Equally important in this revolt, which was unusually

well organized and led from above, is the question of

what made these most conservative elders willing to

risk total destruction. Here the answer is probably a

complex combination of unusual humiliations, the

thwarting of legitimate religious expressions, and

excessive clerical hostility and exploitation, combined

with a temporary relaxation of Spanish control in the

provincial government.

"According to the contemporary chronicler and participant

Fray Francisco Ximénez, the immediate cause for

the 1712 revolt was the harsh exploitation exercised by

the civil and, more specifically, religious authorities.

... In 1710, the long and honored career of the Bishop

of Chiapas, Francisco Núñez de la Vega,

came to an end ... the new bishop, in contrast to his

predescessor, began to enrich himself both through new

church levies and by raising the prices of old ones.

"[T]he moral authority of the local church declined

greatly, as liberal priests were either silenced or

replaced, as was the case with the chronicler Ximénez.

The civil officials also weakened the authority of the

local priests when the latter attempted to prevent

civil and commercial exploitation of their communicants.

Along with the newly intensified exploitation of the

church hierarchy, there was the traditional exploitation

of the Indiand by civil government at the capital of

Ciudad Real. The justica mayor, for instance,

impoverished many a wealthy Indian through false

charges and drawn-out trials. ... Another source of

tension was the ladinos of Ciudad Real who charged

exorbitant prices and indebted many Indian families...

"...[T]he Council of the Indies in Spain, when

suddenly confronted by the uprising of some 5,000

to 6,000 Mayan Indiand, rather ingenuously explained

the cause of the rebellion in terms of the recent

death of Don Martín de Bergara, the alcade

mayor, or civil governor of the province of

Chiapas. The fiscal of the Council believed that:

"'As Don Martín de Bergara ... was the most gentle in all his action, the Indians by these good actions were made to recall the good and evil which they had received from one or another Alcalde Mayor, and realizing what could happen to them with a new Alcalde Mayor they began to spread the word that already they were free, since the Alcalde, who was their King, had died...'" 38

"[O]ne clear indication of the coming rebellion was the increasingly frequent appearance of miracles and other religious manifestations and superstitions... The first manifestations of discontent by the Indians of Chiapas were expressed in religious revivalism. ... [T]here next occurred a series of appearances of the Virgin Mary among the Tzotzils in 1711. ... [I]n the early days of 1712, on the outskirts of Cancuc, it was announced by ... María de la Candeleria that the Virgin had appeared before her and ordered that a shrine be built in her name of the outskirts of Cancuc. ... [T]he young girl soon began holding private discourse with the Virgin and it became an accepted principle that the Virgin would speak to her people only through the young girl...

"The Virgin's appearances at Cancuc had a powerful impact on the region and soon brought multitudes of worshipping Indians flocking to the Pueblo in pilgrimages. ... [A]s was common in these cases, the promoters of the shrine appealed to ecclesiastical authorities for recognition of its legitimacy. But becoming frightened of the increasing number of miraculous appearances, the conservative bishop quickly rejected the claim... and sent local clergy to deal with the situation. ... These ... berated the local fiscales for believing in this false miracle and even attempted to burn the shrine. But the Indians positively prevented this act, and the friars were forced to leave." 39

"By this action, the church cut off legitimacy claims for the new cult, and under the apparent leadership of Sebastián Gómez, who now added the title of de la Gloria to his name, the dissident cult began to mold traditional racial hostility and to adopt the classic revolutionary peasant stance of a caste war of extermination." 40

"In a general declaration of rebellion issued on August 10 and carried to all the towns by special runners, the elders of the Cancuc council proclaimed that:

"'[N]ow there was neither God nor King and that they must only adore, believe in, and obey the Virgin who had come down from heaven to the Pueblo of Cancuc for the sole purpose of protecting and governing the Indians, and at the same time they must obey and respect the ministers, Captains, and officials that she placed in the pueblos, ordering them expressly to kill all the priests and curates as well as the Spaniards, Mestizos, Negroes, and Mulattoes in order that only Indians remain in these lands, in freedom of conscience, without paying royal tributes nor ecclesiastical rights, and extinguishing totally the Catholic Religion and the Dominion of the King, at the same time carrying alms offerings and general contributions to the said image of the Virgin and castigating with cruel punishments all who resisted. ...'" 41

"[T]he leaders at Cancuc ... dispatched 'soldiers of the Virgin' to deal with Spaniards in the area, as well as recalcitrant fiscales who refused to support the movement." 42

"At the acknowledged leading town of the Republic,

Cancuc, great special masses were said and many

ceremonial feasts were held, principally under the

leadership of the young Indian girl Maria de la

Candelaría. The sacerdotal robes of the

expelled Spanish priests were worn by the natives

and the holy chalices and crosses from the church

were carried forth in great processions. In short,

continuity in symbols and form was heavily stressed,

with thechurch now headed by the Virgin Mary instead

of God, and with a heaven and a priesthood open only

to the Indians. As the former fiscal of Guaquitepeque

and later Vicar General Matthew Méndez reported,

Sebastián Gómez declared that 'now the

road to heaven remained closed to the Spaniards who

were Jews because they did not want to believe in all

this [i.e., the coming of the Virgin to Cancuc].'

"To further stress the new place of the Indian, the

Virgin commanded that all Spanish women brought in

captivity to the villages should be wed to Indians."

43

"When Sebastián Gómez and the leaders of Cancuc attempted to spread their caste war against the Spaniards to all the people of the Chiapan highlands, rapid Spanish action and initial Indian indecision quelled potential support and the rebellion quickly burned itself out beyond the lands of the Tzeltals." 44